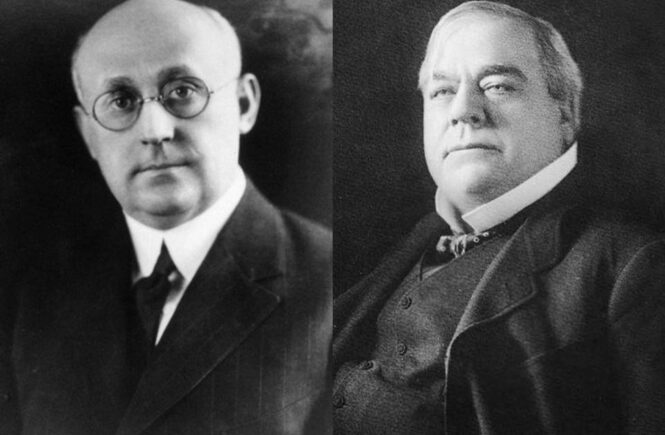

J.C. Nichols and William Rockhill Nelson shared a vision for their city — a vision tarnished by white supremacy.

One Sunday afternoon more than a century ago, an ambitious young home builder named Jesse Clyde Nichols called on Kansas City’s most powerful man, hoping to make amends.

Nichols had recently opened one of his first few residential subdivisions, just southwest of the grand limestone mansion he was visiting. He was there because he’d learned that his names for two of the developments, Rockhill Park and Rockhill Place, had angered the man inside, William Rockhill Nelson, founder and editor of The Kansas City Star.

The butler answered the door and took Nichols’ card. He could see Nelson at the end of a long hallway, in his study. But when the butler returned, he handed Nichols’ card back and said Nelson wasn’t home. The following Sunday, Nichols returned with his wife and made it through the door, according to the story told over the years by his son, Miller Nichols.

Whatever resentments Nelson harbored about Nichols’ clumsy attempt to trade on his name were set aside. What began instead was a friendship and mentorship based on a shared vision of their city — a vision tarnished by white supremacy.

In Nichols, 40 years his junior, Nelson saw a protege who could continue the work of a national social movement that his Star had relentlessly promoted, called City Beautiful. Kansas City would be a place of lush green boulevards, parks, grand fountains — and segregated residential neighborhoods.

Nothing in the surviving record paints either man as a virulent racist. But like most powerful men of their time, they viewed the world through a white lens, and saw segregation as a necessity for a cohesive, ordered society. In the world of real estate, that meant homes built with restrictive covenants — documents that dictated not only the details of design and construction of homes, but who could live in them.For Nelson and Nichols, “segregation of the races, like segregation of economic classes, was both a fact of life and an essential means of defusing sectarian conflict,” wrote Harry Haskell, grandson of Star editor Henry J. Haskell, in “Boss-Busters and Sin Hounds: Kansas City and Its ‘Star,’” his history of the paper.

Their relationship would last less than a decade, until Nelson’s death in 1915. But its legacy rippled across the decades in Kansas City, laying the foundation for a system that denied Black families access to a housing market that created wealth for generations of white families.

Nelson’s support provided Nichols a critical early boost, helping pave the way to a 50-year career in which he built homes and apartments for tens of thousands of Kansas Citians. The painstaking design of his neighborhoods, from Armour Hills to Prairie Village, all included covenants with racist clauses.

Nelson also gave the young developer technical help, as his foreman lent equipment to help Nichols pave his streets. “He was an ardent believer in better residential areas, and better planned cities,” Nichols wrote years later in an unpublished memoir. “He encouraged me greatly by telling me that anything would be better than the use of the land made by the pre-Civil War owners.”

“As a matter of record, he learned the real estate business almost literally at Nelson’s knee,” Haskell said.

The two could not have been more different. Nelson, known as “the Colonel” — for his commanding presence, not military service — was bombastic, arrogant and headstrong. The Star, which he founded in 1880, was his cudgel, and he wielded it to get his way in the business of the city.

“Remember this,” he said, “The Star has a greater purpose in life than merely to print the news. It believes in doing things.”

Nichols, owlish and reserved, turned home construction into a science and created a template for the modern American suburb. While many others contributed to the creation of residential segregation, his influence was overwhelming.

“No person accelerated white flight, redlining, and racial division in the Kansas City area more than J.C. Nichols,” Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas said earlier this year.

And among those enabling Nichols was the founder of The Kansas City Star.

‘WHERE DISCRIMINATING PEOPLE BUY’

Nelson is best known as a newspaperman who crusaded for clean government, publicly owned utilities and economic growth. But, like Nichols, he was also a real estate developer.

“Building houses,” he once said, “is the greatest fun in the world.”

He built them — many for Star employees — on land north of Brush Creek and just south of his Oak Hall mansion, now the site of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. The neighborhood was called (what else?) Rockhill.

And, like Nichols, his homes came with racially restrictive covenants, according to historian William Worley, author of “J.C. Nichols and the Shaping of Kansas City.” The only difference was that Nelson’s expired after a period of years; Nichols’ did not.

Nichols’ first major development, the 1,000-acre Country Club District, came with a detailed list of requirements for home builders and buyers.

Among them:

“OWNERSHIP BY NEGROES PROHIBITED:”

“None of the lots hereby restricted may be conveyed to, used, owned nor occupied by negroes as owners or tenants.”

Nichols was not the first to employ racially restrictive covenants to control his neighborhoods. But he was the first to incorporate them with a self-perpetuating renewal process. His systematic use of the tool, on such a broad scale, spurred other developers to do the same.

Nelson never invested money in Nichols’ ventures. And Nichols wasn’t hurting for cash. By age 29, he was a director of the Commerce Trust Co. and had an $800,000 line of credit along with a group of investors. But Nelson provided something just as valuable: favorable coverage in the city’s most influential daily newspapers. He also reaped profits from the countless pages of advertising that Nichols purchased.

The Star chronicled Nichols’ progress in detail, covering every land transaction that led to what became the Country Club District. Even his 1908 case of typhoid fever merited a brief article.

Nichols’ ads in The Star were far more genteel and coded than his covenants, but they conveyed the same message. They beckoned readers to visit the “highly restricted” Country Club District, “A Place Where Discriminating People Buy.”

An advertisement in The Star in the early 20th century promotes J.C. Nichols’ Sunset Hill development, billed as “The Most Highly Restricted Part of the Country Club District.” File THE KANSAS CITY STAR

A November 1913 ad described the district as “the most beautiful residence section in Kansas City” because it will “retain its exclusiveness forever — the only one so carefully safeguarded that it will permanently withstand all conditions that deteriorate property values and injure the individuality of homes.”

One fawning article in July 1909 expressed astonishment that the young businessman could have come so far, so fast.

“He became a real estate operator with 1 1/2 million dollars behind him to spend in the development of 1,000 acres of land in the same time that it would take the average man to reach the position of confidential clerk in a rental agency.”

“Nelson was signaling, in the clearest possible way, that he regarded Nichols as his designated successor at the helm of the City Beautiful brigade,” said Haskell.

A PARTNER IN D.C.

Nelson and Nichols were not alone in creation of a starkly segregated city. Local, state and federal housing policies were all drivers. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), created in 1934, essentially codified residential segregation by refusing to insure mortgages in and around Black neighborhoods, the practice known as “redlining” for the color-coded maps the agency used.

It also subsidized creation of whites-only subdivisions, stipulating in its underwriting manual that “incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities.” Nichols, as a member and leader of the National Association of Real Estate Boards, had a role in developing the guidelines.

In May 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racially restrictive covenants were not legally enforceable. The decision was in response to a case brought by Black families in St. Louis, Detroit and Washington, D.C., that had been barred by court injunction from living in houses they’d purchased in white neighborhoods. But the court also said that the covenants were valid if homeowners complied with them voluntarily.

The Star ran the story on the front page in its lead right-hand news column, but made no mention of Nichols. His position didn’t change. Six months later, the paper carried a story on his comments to the real estate board, where he maintained that “legally binding private restrictive covenants should control residential neighborhoods.”

Nichols died of lung cancer on Feb. 16, 1950. The Star and Times filled their papers with tributes and biographical pieces.

“A great vacancy has come into the life of Kansas City,” said an editorial in the next day’s Star, which praised his “work and wizardry.”

“Nichols stands as one of the very few city leaders of vision that carries beyond his time.”

In this, The Star was spot on.

‘RACISM DOESN’T TAKE A DAY OFF’

Nelson and Nichols left behind a city with two housing markets: one for Black people and one for white people.

Even with the advent of open housing laws, white real estate professionals would refuse to show Black families homes in certain neighborhoods. Advertising in The Star underscored the color-conscious system. Ads were always careful to specify properties as east or west of Troost, the avenue that had become the city’s de facto boundary of racial separation.

Lewis Diuguid, who worked at The Star from 1977 to 2016 as a reporter, columnist and editorial writer, remembers his former mother-in law’s struggle to buy a home in south Kansas City in the late 1990s. Even then, he said, she encountered resistance from real estate agents when she wanted to see certain properties.

“Racism is resistant to change,” Diuguid said. “Racism doesn’t take a day off. It doesn’t take a holiday; it doesn’t take vacation. It is constant and mutates to change with the changing time.”

The restrictive covenants, said CEO and president of the Urban League of Greater Kansas City Gwen Grant, are “an example of structural racism,” and are one piece of the layer of policies that have been designed to suppress Black people.

“The impact is systemic, and it’s impacted all aspects of quality of life and economic mobility,” Grant said.

Today’s underlying economic problems can be traced back to slavery, Jim Crow laws, segregation and restrictive covenants. Those policies trapped wealth in a bubble for one group of people.

U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver said the fallout from the restrictive covenants can still be seen by looking at Kansas City’s housing patterns today.

“People always want to say that because they didn’t have slaves, they aren’t at fault for where Black people are today, Cleaver said.

“That’s true,” he said, “but they benefited from it.”

Conditions have improved somewhat.

In 2000, a Brookings Institution analysis reported that Kansas City had a segregation index of 70.8, representing the percentage of the city’s Black population that would need to relocate to be fully integrated across the city’s neighborhoods. It was the nation’s 11th highest among cities. By 2017, with Black people moving into the suburbs, that percentage dropped to 59.5, and the city’s position dropped to 27th.

This spring and summer, the United States faced a reckoning over its systemic race issues as people across the country demanded change. In Kansas City, thousands turned out to protest.

And in the weeks following the protests — which still continue, though they aren’t always as visible — Nichols’ name was removed from the fountain and boulevard near the Country Club Plaza he developed. J.C. Nichols Parkway and Memorial Fountain are no more.

As part of its coverage, The Star published an editorial about Nichols that would never have appeared in Nelson’s day as publisher or in the many decades to follow.

The headline began: “J.C. Nichols was a racist.”

The Star’s Judy L. Thomas and Matt Kelly contributed to this story.